The Wrekin, England

On August 8th, 2016; I hiked up onto “The Wrekin” in England. Wrekin Hill, near Telford in Shropshire, is said to be the oldest hill in England, and was reputedly used by J.R.R. Tolkien as inspiration for Middle Earth in “The Lord of the Rings”.

The 1,300 ft. hill is made of volcanic rock.

During the late Precambrian period, Shropshire lay under a shallow sea, and earthquakes formed major faults in the Earth’s crust.

The Wrekin is very close to the largest fault, the Church Stretton Fault. The location of the vent that deposited the molten rock and ash that created the Wrekin is unknown.

The crest of the Wrekin’s ridge and its northwestern slopes are formed from various rocks of volcanic origin assigned to the Uriconian series, of Precambrian age. From the picture above, looking onwards is the Shropshire. There, the exploitation of coal and iron ores represented two of the very earliest industries in the Gorge, dating back to medieval times. These ores were laid down in the Carboniferous Period, about 250 million years ago, when much of Shropshire was covered in tropical swamps and forming a Bog-Iron and coal deposits.

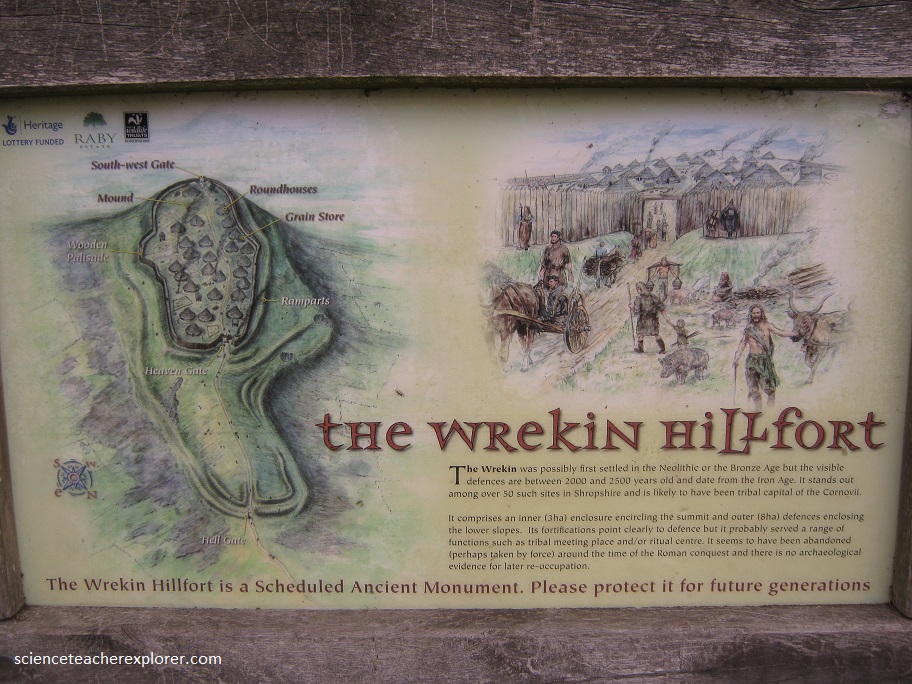

Additionally, “The Wrekin” is a location of an archeological site called the Wrekin Hillfort. The picture below explains its history in detail.

Just a few kilometers southwest of the Wrekin, I visited the “Iron Bridge”.

If any-one object marks the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, it is the graceful span of the eye-catching iron bridge in the town and the gorge to which it gave its name. With a central span of 100 ft., the bridge was erected in 1779 and was a rapid feat of construction built within 3 months, without hampering the passage of boats on the river in the least. A leading local ironmaster, Abraham Darby, had invented a new process for smelting iron with coke instead of charcoal, which enabled it to be produced much more cheaply and quickly. The Bedlam furnaces for this process is found within a half a kilometer up the river from here.

Pictured above, the brick and stone remains are the Bedlam Furnaces, built in 1757 to smelt iron from local ironstone. Their construction corresponded to a time of extraordinary expansion of the ironworking in the Gorge. the furnaces themselves are notable for having been among the earliest examples of blast furnaces which were designed to use coke fuel, rather than coal, a practice made possible by Abraham Darby I’s revolutionary discovery in nearby Coalbrookdale in 1709. They are also important for their early use of a steam engine (called ‘fire engines’) to raise water to drive the bellows for the air blast.

Nearby the Bedlam Furnaces is Birmingham, where I was able to visit the “Thinktank” at the Birmingham Science Museum.

Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum has a big collection of Steam engines. I was focusing on the Smethwick Engine that is housed there. This is the oldest working engine in the world, designed and built by James Watt in 1779, and was in use until 1891.

When James Watt designed the Smethwick Engine in 1778, it was the most efficient engine of its time. Today, it is the oldest working steam engine in the world.

From the 1760s canals transported goods from Birmingham to the West Midlands, around Britain and –via the ports–to the rest of the world. But at Smethwick there was a problem. The area was hilly. Each time a lock was opened to allow boats over the hill, 110,000 liters of water flowed out–leaving less and less water in the canal. At times, only 50 boats a week could travel through Smethwick. The only way to make sure there was enough water was to pump the water back up to the top. Everyone agreed that a pump would do the job–but it needed a powerful and efficient engine. Existing steam engines designed by Thomas Newcomen were expensive to run as they needed a lot of coal.

James Watt found a way around this. He designed a steam engine that was twice as powerful and three times more efficient than the Newcomen engine. Newcomen’s engine worked by cooling steam in the cylinder. Watt improved this design by condensing the steam outside the cylinder in a separate condenser. The Smethwick engine was put into use on May 29th, 1779. Soon, 250 boats a week were passing through Smethwick and, via the River Severn and Mersey, to the world beyond. The engine ran for the next 112 years.

The Smethwick Engine can lift one tonne of water every stroke. It took 35 men ten months to build the engine and engine house, with walls 70cm thick. Assembled on site, it cost 2,000 pounds, (750,000 pounds at today’s prices).

The governor maintains the speed of the engine by regulating the amount of steam admitted. If the speed of the steam engine increases, centrifugal force moves the balls out and a rod closes a steam valve until the engine has slowed down. As the balls decrease in speed, the rod moves again to open the valve and maintain the correct speed.